Description

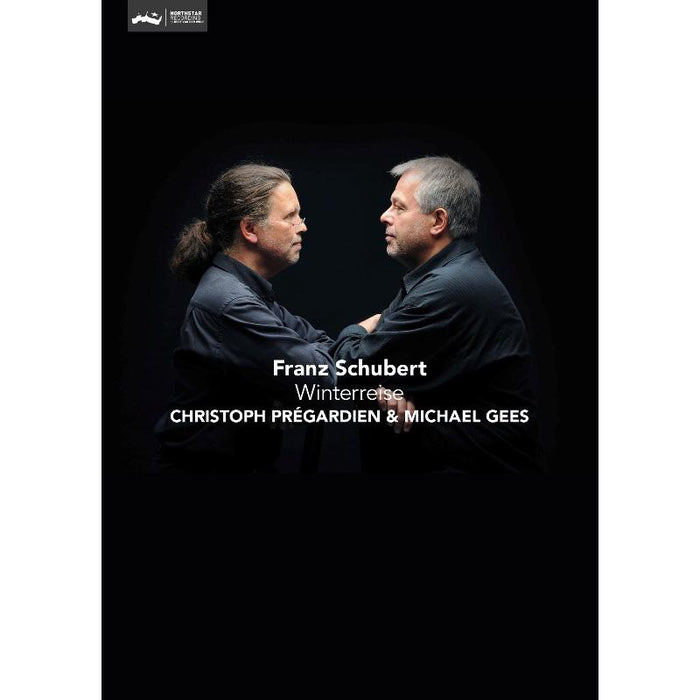

Tenor Christoph Pregardien and pianist Michael Gees perform two of the greatest masterpieces in the solo song repertory: Schumann's Dichterliebe and Wagner's Wesendonck Lieder. Schumann's powerful, but lesser known Lenau Lieder with Requiem, Op.90 completes the album.

Robert Schumann was the most confessional of composers and many of the songs from his great Liederjahr of 1840 were in essence love songs to Clara Wieck. In Dichterliebe ('Poet's Love') Op.48, he turns again to the pithy verses of Heinrich Heine's Buch der Lieder. On one level, Dichterliebe can be heard as his most piercing recreation of the fluctuating emotions he had experienced during his long courtship of Clara. Characteristically of Schumann, it is the piano that controls the musical narrative in Dichterliebe. Characteristic, too, of Schumann's 1840 songs is the piano postlude that encapsulates and deepens a song's meaning. Dichterliebe takes this to the furthest extreme.

In August 1850, Schumann set six poems by the unstable and ultimately insane Austrian poet Nikolaus Lenau (1802-1850), whom he had briefly met in Vienna in 1839. Like Schumann and Wolf, Lenau spent his last years in an asylum, his mind destroyed by syphilis. Schumann was ill and dejected at the time, and his mood is reflected in these poems of satiety, oppressiveness and transience. As a tribute to the dying poet (who he initially believed had already died), Schumann appended to the Lenau group one of his rare religious songs: Requiem, a setting of Héloïse's lament for Peter Abelard. For this quasi-operatic music of solemn grandeur and mounting exaltation, Schumann devised a swirling keyboard accompaniment that takes its cue from the poem's image of angelic harps.

During the autumn of 1857 Wagner began a set of five songs to poems by Mathilde Wesendonck, written in evident imitation of Wagner's hothouse Tristan manner – one of the very rare occasions when he set words other than his own. The Wesendonck Lieder, as they are now known, were revised and completed in 1858, and first performed as a cycle in July 1862 at a country house belonging to the publisher Franz Schott. Each of the songs shares with Tristan the concept of 'endless melody', a saturated, dissolving chromaticism – the musical emblem of unstilled desire – and a feverish, oppressive atmosphere.